He sits before the window at his desk writing. The soft gray light of a rainy, April afternoon shows faintly, ethereally into the room. The house is quiet.

It is difficult to know what he thinks as he scratches upon the yellow pad his last few impressions.

He has failed with his sons, who despise him for everything he did or did not do for them. He remembers how he spanked them when they were children, rewarded them for good report cards in school, and when they grew older lent them the car on weekends. He remembers not taking them fishing, and coming only seldom to their school sporting events. He prodded them into college, and finally into the insipid, vacuous lives they now led.

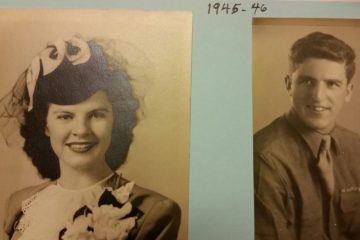

His wife lives in San Bernardino and he hears from her at Christmas by card, her name stamped in gold Gothic letters at the bottom, and he hears from her through her lawyer whenever the check is late. But he remembers the first time he saw her, how lovely, how ideal she was. He remembers how perfect it all was then, before they had money, before they could afford everything they always thought necessary to live a happy life.

Dana…he remembers her also. She found a man drowning himself in the after work cocktail lounges, drowning his past and about to begin on his future. He was closing the doors, all of them, until she had taken him home, dried him out, washed, fed and dressed him, and had sent him back out into life. She had done all this for him, and yet still could not fully grasp the loneliness, the sense of failure he was suffering.

He had called her only an hour ago in Detroit.

“That you?” he whispered into the phone.

“Silly! Yes it’s me.…are you okay?” It felt better just to hear her voice.

“It’s raining out here. I’m sitting in this house by the window watching it rain. How are you, love?”

“Fine… sure nothing’s wrong? Want me to drive out?” She was onto his mood, beginning to know him pretty well.

“No, fine…don’t bother. Just wondering what you’re doing, how are things in the city? Doing nothing much myself. Can’t get interested.” He lied.

“I don’t think I’ll have much work this weekend. I’ll probably be out Friday evening. Do you miss me?” She was beginning to relax now.

“As always.” He couldn’t think of what else to say, couldn’t find any words. “Friday will be fine. I’ll talk to you then.”

“Okay, I’ve got to go now anyhow. Love you.”

“Me too.” He listened to her line go dead somewhere on the forty-fifth floor of the RenCen Tower 300, on the riverfront. His phone went dark, he tossed it on the desk and reached for his drink.

That was an hour ago. He had finished writing on the yellow legal pad and set the pen next to it on the desk. He stared through the window out at the blurred patterns of trees rolling in the cold, wet April wind. Bits of sleet and rain tapped lightly on the glass, like the long, delicate nails of a woman’s slender fingers.

He smiled to himself as he thought of that idiotic Christmas card that would not come next December. And for some reason, the idea occurred to him that he didn’t know why he had never gone fishing.

The afternoon light had gradually died and turned to evening, and he was sitting in the dark. He felt for the bottom drawer of the desk, opened it, and reached for something toward the very back.